Soul Erosion in a Counterfeit World:

The definitive film of the 1980’s

William Friedkin’s career masterpiece

To Live and Die in L.A.

MGM/UA, 1985

4 stars out of 4. Immortal classic film.

As a lifelong fan of The French Connection (likely still the best film ever made about the police) I use none of the words above lightly. Over the years I find myself returning to this film and its ideas, themes and context. It has never truly gone away and is arguably more relevant today than upon its original release. TLADILA is a bold, brash and unrelenting explosion of energy, drive and complete erosion of the soul. This soul erosion is a reflection of the shift in culture that occurred and defined the 80’s, and an extension of Reganomics itself. It goes without saying that the industry itself was turned inside out for the worse but combined with the rise of commercialism in every aspect of society, conglomerates amassing huge amounts of control over our daily lives amidst a general feeling that cash solves all problems. It is no wonder that the film itself deals with a counterfeiting plot.

The film deals with the US Secret Service and their everyday activities fighting against counterfeiting rackets as an extension of the US Treasury department. Agent Richard Chance (the astounding William Petersen) is a reckless and brash field agent who risks everything in the pursuit of his target. When his retiring partner is ambushed and killed by ultra-counterfeiter Rick Masters (the incomparable Willem Dafoe), Chance sets out to nail Masters by any means necessary, roping in a new partner the by-the-book John Vukovich (John Pankow). Chance’s enraged pursuit, backed by a scintillating ego will place absolutely everything in the crossfire.

Chance is perhaps the worst agent possible. He must live on the edge almost as if it is as essential as breathing and frequently risks everything in order to achieve his goals. With the murder of his older partner pushing him over the edge, now the law he has upheld his entire career is merely an obstacle that slows him down. His partner Vukovich is another obstacle, as a traditional agent who finds Chance’s actions more and more objectionable though he himself gets involved deeper and deeper running against his own moral code and perhaps beginning to enjoy the danger somewhat.

Rick Masters is also not a typical villain. He may be even more of an enigma than Chance. As an artist he is consistently searching for something to fill the empty void within himself, the same degree of counterfeiting displayed in his excellent false money. This is why he burns all of his work, as it reveals something he cannot or will not acknowledge about himself. The same reasoning applies to the consistent videotaping of his own sexual encounters with his girlfriend. It is an extension of how each character displays such a deep rooted sense of teetering on the edge of destruction due to the fact that only primordial reasons guide them forwards in a land of imposed annihilation.

All in the film are completely developed and morally questionable characters, amidst a world that burns away at them. Frequently it seems as if everyone in the film is treading water in a sea of acid all while trying to grasp at any shred of debris to stop their flesh burning away. The style and tone of the film completely predates the slightly later 80’s action film renaissance where character began to take a backseat to unrealistic glories which when closely examined feel quite hollow i.e. the Rambos, Miami Vice-styled crud and even predates many of the same themes that turned up in Lethal Weapon and Die Hard before those franchises became imitators of themselves.

Each and every one of these characters is morally questionable and absolutely duplicitous. It is up to the audience to determine when they are counterfeit or if they are completely gone. The character of Vukovich is perhaps the only one who is not too far gone but over the course of the film even his motives come called into question. Friedkin described the film as being set in a counterfeit world, where everyone and everything is as counterfeit as the money Rick Masters makes. But this can only take place once the soul has eroded away leaving a world of people who revert to primordial tendencies of greed and rage with a degree of conviction because they have nothing else left to them. It is this central emptiness to their lives that pushes Masters to continually burn all of his own artwork as he cannot face the fact that he is already a dead man, and the reason why Chance lives so close to the edge taking enormous risks without any hesitation.

Friedkin was and is what I describe as a kinetic filmmaker, or one who uses the medium to convey a sense of motion and immediacy through sensory linked visuals in addition to narrative. You see this in The Excorcist and The French Connection, but never as blatant and layered as TLADILA, where they begin in the opening titles. It may come across as heavy handed to some, but they serve to link the narrative to the individual character’s state of mind and also to disorient the viewer and forcing the brain to work harder to get the meaning thus involving the audience in the picture even more. That this is done in a refined way without any modern tendencies to induce false realism only adds to the picture’s power. This extends to the soundmix design which uses varying levels of volume and other trickery to create a sense of unease in the brain that puts the audience on edge. And to extract such a degree of control on a low budget film in the era of analog Dolby Stereo, which was extremely limited in terms of what you could and couldn’t do, is nothing short of amazing.

Seeing this film begs the question: “how in the world did they get away with all this?” The answer is simply that it was made as essentially an indie with a non-union crew, and where everyone took pay cuts to simply do the film. Budgeted at six million, TLADILA was never meant for star power, and thus actually cast for the respective parts using lesser known stage and screen actors. It is of course no surprise that many are familiar faces now since much time and care was placed in finding the right people to fill the roles. Particularly Petersen and Dafoe both of which are absolutely riveting, with Petersen presaging his phenomenal work a year later in Michael Mann’s stylistically similar/outright inspired by TLADILA, Manhunter. (Mann later tried to sue Friedkin by claiming TLADILA stole from his developing Miami Vice series. Which it didn’t, as Vice was a poor man’s version of TLADILA, made for TV.) Then you have Friedkin’s usage of all practical locations and no sets. This bridges the line between fiction and reality so that we’re already in the film’s world and it is our own. To add to this it was Friedkin’s desire and practice during shooting to secretly film rehearsals and not cut at scene’s end in order to try and catch those magical moments of realism that came from developing a real trust with all the actors. The film truly evolves into a nightmarish vision of what seems like just another chapter in the madness of humanity.

The film was shot fast and dirty, but still provides remarkable cinematography from Robby Muller with great usage of color and staggering tracking shots that directly recall TFC. The editing is seamless and editor Bud Smith actually co-produced the picture. (I met Mr. Smith once at a lecture; who aside from being very honest, informative and talented is a very nice man. All a rarity in the business.)

The other and perhaps best stroke of luck possible is that the film’s deal was moved to MGM/UA who at this time was still financially off kilter, and UA had been bought out after the Heaven’s Gate fiasco. This led to many things being virtually unquestioned until it was far too late to do anything and because the budget was so low less care was placed on messing with Friedkin’s decisions. This was challenged in the ending, where the studio objected to the abrupt reversals and demanded a more conventional and absolutely implausible happy ending. That being said is a testament to all those involved that they could craft such a piece of garbage and tie it in beautifully to the film’s overlying tone.

Anyone who knows of the film today or remembers it is usually referring to the now renowned car chase that tears through backstreets, train yards and the LA aqueducts before finally heading down the freeway against oncoming traffic. It is as bold as the film itself and was inserted only as Friedkin put it: “if it could top the chase in The French Connection”. Due to the latter’s sheer iconic status it doesn’t exactly do that, but it is one of the rare chases that so perfectly matches the story and characters with reality. Every single aspect of this chase is down to earth and places the audiences right there in the moment with Chance and the panicked Vukovich in the back of a crap Chevy sedan at its breaking point. Friedkin went for broke here and rightfully so. Car chases have become a cliché and never serve anything other than being the umpteenth bad action scene in any standard filth. They used to mean something and the really good ones told you about character whilst performing vehicular feats you could only dream about doing. Thus this chase is up there with the greats from TFC, The Seven-Ups, Ronin and of course the big one: Bullitt.

Now we come to the score. Friedkin handpicked Wang Chung to score the entire film as he liked their sound on the Points of the Curve album and felt they would be perfect for the setting he was trying to achieve. While it seems to be off-putting to modern reviewers who lambast the sounds as being terribly dated, in fact Friedkin was right and not only is the score perfectly matched to the narrative, but it is the best work the band ever achieved-particularly before going down in history as the “everybody wang chung tonight” guys. It is a symphony of darkness in a sun-blazed world set against synthesizers. Even their earlier hit “Dance Hall Days” was incorporated into the film as what its eventual resting place likely was: background music for a seedy stripclub in the daytime hours.

Modern viewers complain about the film’s style and staging being severely dated, but this misses the point entirely. The goal was to fully utilize the new sheen of the 80’s to fully convey just how far gone society had become. It is all defined by the erosion of the soul I underlined. It beautifully hints at the film industry shifts occurring at the time, the dark underbelly of Reganomics and the growing desire at the time for more.

The gaze of Regan himself reaches into the film, as a framed portrait on the wall of the abandoned Secret service branch office, glimpsed as Chance and Vukovich return arms late at night. It is one of those real life touches that so eloquently underscores the film’s study of the difference between outer shells and true intent. Regan is of course also heard in the opening, where he is giving a speech and heard over the radio comms.

Friedkin is still working today, but never achieved the recognition or career of some of his contemporaries, likely due to his up and downs at the box office and his somewhat abrasive personality. But it cannot be stressed enough that he is a prime example of someone who truly cares about the medium and isn’t afraid to embrace cinema history or to break rules. Somebody PLEASE give the man a decent budget and free reign. TLADILA was his return to form, and essentially going back to his roots of independent documentary filmmaking. It remains a triumph of story, style, execution and complete mastery and control of narrative cinema—particularly after the absolute waste that was his film Cruising.

TLADILA is a film not easily forgotten, and if closely examined reveals a rich understanding of the human condition and how it our own impositions that tear away at the soul. It is practically The Third Man of the 1980’s.

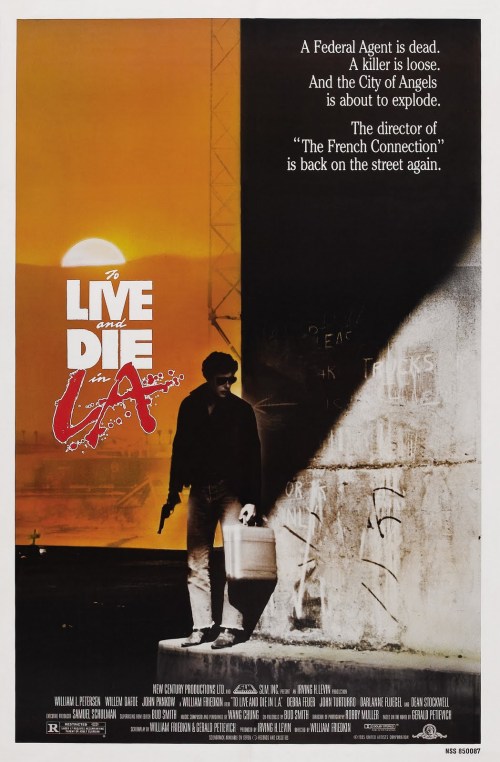

A federal agent is dead…

A killer is loose…

And the City of Angels is about to explode…

EDITIONS:

Not much to report here. Image eventually released a decent LD with okay color, widescreen matting and the original Dolby Stereo mix in PCM. MGM finally released the DVD in 2003 with extras and commentary surprisingly. The sound was remixed in 5.1 but preserved the original intent and design thank goodness. Eventually a Blu-ray was released and thankfully it features no tweaking or revisionism. The color and contrast is remarkably improved providing for likely the best presentation since the film’s 35mm run in 1985. The 5,1 remix was upgraded to a lossless DTS-HDMA presentation and is lovely. I only wish they had also included the original 2.0 track in lossless. Stupidly this disc has no new features nor any of the previous SD features so one must keep the DVD for those and swap discs to enjoy them.

Also of note, the DVD and Blu-ray releases stupidly and pointlessly airbrush out Petersen’s silhouetted face from the stunning poster and substitute a generic one. What the heck MGM?!?!?

SOUNDTRACK RELEASES:

Wang Chung’s score was released on LP and CD, arranged into a vocal side and instrumental side. I haven’t heard the CD as the vinyl is phenomenal and can be had four typically under two dollars. It was mastered at Artisan studios in LA just as their other records for Geffen were, so you have really the pinnacle of great 80’s production, engineering and plating going on to produce great records. The mix is far better than the film version and the album is a great listen for any mood. Sadly it does not include “Dance Hall Days”, but this can be rectified with one of the many 7” or 12” single releases of the song, or an LP copy of Points on the Curve, the album that convinced Friedkin that they should score the film, and it also includes “Wait”.

I recently found a 2015 dated vinyl reissue from Geffen of the film’s score in stores, but have no idea as to its origins or cutting information. If the price falls enough I will try it out, but don’t expect anything to touch the original LP, nor it be something that would justify the nearly $30 price difference between the two.